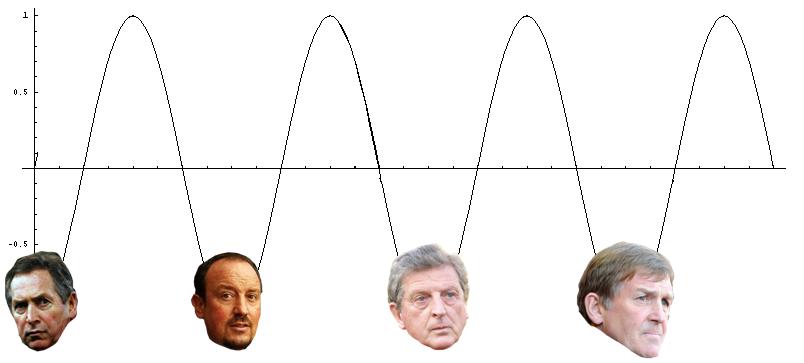

On Sunday Kenny Dalglish's Liverpool lost 1-0 to West Bromwich Albion, consigning the Reds to their ninth defeat of 2012. For Baggies boss Roy Hodgson this wasn't entirely unfamiliar; in his brief spell in charge of the club they also lost nine games. The mood at Anfield was totally at odds with that at the end of the 2011/12 season, where Dalglish's side had moved from 12th to 6th following the departure of Hodgson.

- Newcastle: £10,000,000

- Everton: -£12,000,000

Regression Towards the Mean

Flip it, and record the result. Repeat. Once you get three tails in a row, change your socks. Then continue flipping the coin. In particular, look at the three results after you changed your socks. Are they still all tails? Continue flipping the coin, changing your socks after every three tails. You might need a lot of socks.

I ran this test, using a random number generator, to simulate 250 flips, and found that of the 22 times three tails came up, three more tails popped up afterwards 3 times. You should find that the three flips after you've changed your socks, on average, will all be tails 1/8th of the time. So, an overwhelming 92.5% of the time, changing your socks improves the likelihood of heads occurring, right?

I'm sure you think, and probably see why, this is such a ridiculous conclusion to draw; changing your socks has nothing to do with the results of the coin toss. If you have noticed this: congratulations, you're one step ahead of the sports industry.

The Sports Illustrated Jinx

In America, it is a widely-held belief that whenever someone appears on the cover of national magazine Sports Illustrated they will then experience a downturn in luck. There might be some truth in it; cover stars do worse, on average, after their cover appearance then before, although clearly this isn't an absolute rule: Michael Jordan, for instance, appeared on 49 covers. And he had an alright career.

However, the real reason behind the "jinx" is regression to the mean. If you always recognise a sportsperson when they're at the height of a good run of form, then the majority of times they will perform worse afterwards. To rephrase this using our previous example, imagine that getting three tails in a row is the equivalent of having a good run of home-downs, or touch-baskets (or whatever they're aiming for in American sports). And imagine that changing your socks is like being put on the front of Sports Illustrated. As we have previously demonstrated, you will find in the long run that you're not that likely to continue your run of good form (tails) afterwards. (For an explanation of why this is a valid comparison to make, see the Appendices).

English football doesn't have its own Sports Illustrated (for instance, FourFourTwo, the main football magazine, often chooses its cover stars in advance, rather than plucking them at the height of their form). Instead, regression to the mean manifests itself as the bane of managers all over the country.

English Football

Imagine that our coin-flipping experiment represents the results of the matches of the club you support (again, see the Appendices for an explanation of why this is a fair comparison), and tails are defeats. Your club has Milan Abramovic as owner, and he has decided that after three defeats, he is always going to change his socks - sorry, I mean he's going to change his manager. He's going to find that about 7/8th of the time, he is an inspired genius, whose managerial musical chairs is a marvelous innovation.

You should be able to explain to Milan why he's not that smart; although I wouldn't advise you to actually do it, unless you're partial to Polonium-210.

In other words, if you change your manager when the club is suffering a bad run of form, then the majority of times, this change will work. However, this change will have happened anyway. This is also known as confirmation bias. You're essentially comparing two random sets of results (before and after the sacking); however, you're biasing the test by ensuring that one of the sets (before the sacking) is only full of bad results.

Conclusion

Of course, this effect will be less pronounced in real life than it is by our coin experiment; managers do have different levels of ability, some are better than others. However, this exercise in probability should give a better idea as to why teams often turns themselves around under a new boss.

Note that in our introduction, the three bosses whom we mentioned had particularly good starts to their manager jobs at new clubs were all initially caretaker bosses (Dalglish, Hiddink, di Matteo). This isn't surprising, as caretaker bosses are going to be judged over a smaller sample of games (the remainder of the given season; whereas most bosses will be judged over a whole season) and therefore there's more scope for a statistical anomaly.

Sources

Books

Why England Lose & Other Curious Football Phenomena Explained - Kuper, S & Szymanski, S - this book neatly shows why sports results can be compared to random events, particularly with the England football team.

The Tiger That Isn't - Blastland, M & Dilnot, A - contains an explanation of regression to the mean.

Websites

Wikipedia - used to double-check teams' transfer spending, league results, and other facts.

Appendix - why we can model sports results on random events

This is a bit more technical, which is why I've hidden it as an appendix.

As mentioned in the article, some managers are better than others; and players and teams are better than others. However, for a reliable way of comparing these, you need to be able to look at long-term averages. This is perhaps why there is more of an ingrown dependence on statistics in cricket than in most other sports; rather than looking at current form, as most do, cricket players are usually judged by their career averages, so the statistics are more reliable.

If you take a team, they will have a long-run average. Take for example the England football team. If we treat a draw as half a win, over their history they have won 69% of their games. However, the short-term will see random fluctuations in form. It has been shown that these results are indistinguishable to a series of coin-flips where heads is likely to crop up 69% of the time. If short-term form wasn't random, you'd expect far more unbroken chains of wins or losses than actually occur.

So to relate this to the Sports Illustrated Jinx; just because these are athletes whose are usually at the top of their sport, they will still see fluctuations in their form. As the jinx is looking at how their form decreases in relation to their previous form, rather than their long-term form, this is where the misunderstanding has risen from.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed